Education has long been a crucial component in assessing development trends over time and across countries. It has a wide range of consequences, from reducing poverty and inequality to preparing the path for long-term economic prosperity. Higher pay, social mobility, practical life skills, increased discipline, and a readiness to change are all advantages of education.

India’s literacy rate is lower than that of other South and East Asian countries. In terms of literacy rates, India is ranked 19th among Asian countries. According to the World Bank’s Learning Poverty Index, 55% of 10-year-old Indian children are unable to read a basic phrase, compared to 15% in Sri Lanka and China.

Despite Bangladesh and Nepal historically lagging behind, Bangladesh, Nepal, and India have now nearly equaled their female literacy rates at 85 percent.

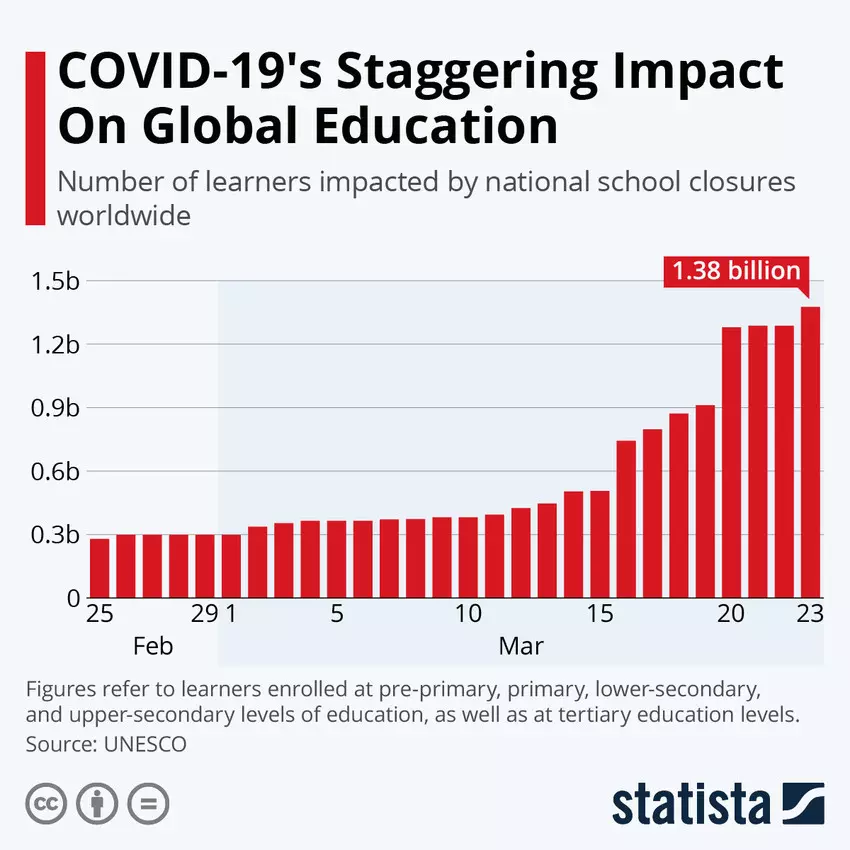

School Closures and Inequalities in Online Learning

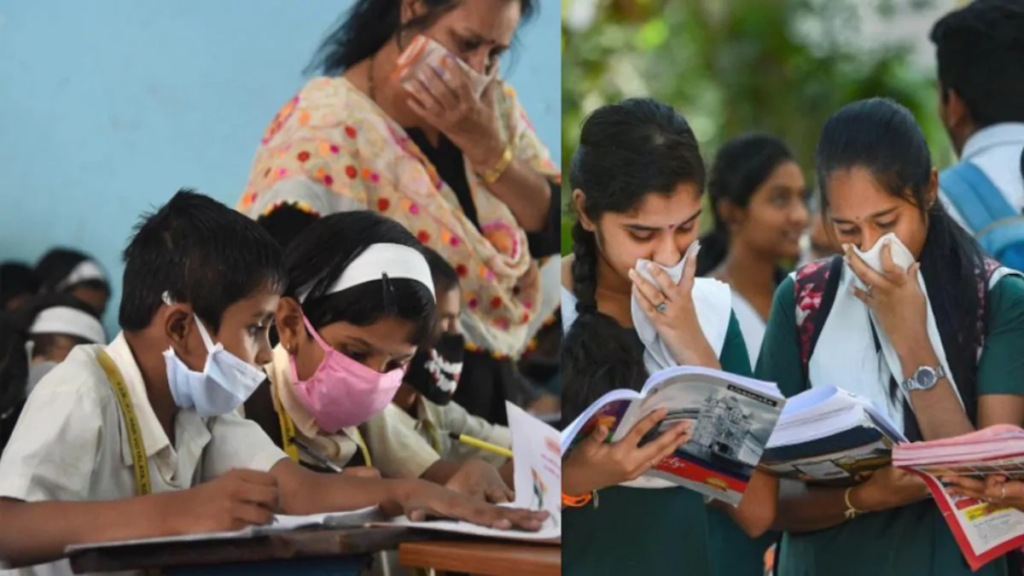

India’s dismal educational records have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with schools suspended since March 2020.

Since the March 2020 lockdown, 1.5 million schools have been closed, and 247 million primary and secondary pupils have been out of school.

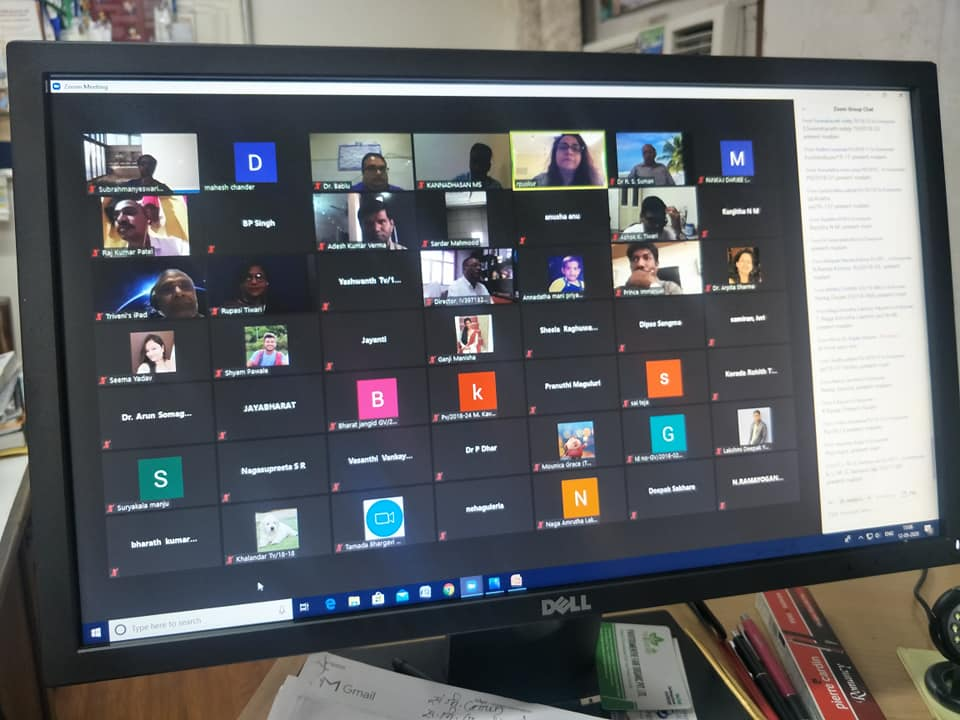

Schools have been attempting to replace in-person classes with online learning since most primary school pupils have not attended school in over a year. Teachers and institutions have tried a variety of methods to communicate with their students, including using television, radio, WhatsApp groups, group tutoring, and Zoom. Loudspeaker tutorials for individuals without internet access are another unique technique to reach pupils.

These online lessons have had a mixed response. While many children in metropolitan regions have access to online classes, many preferred lectures “in a classroom,” where they would not be forced to “do everything on WhatsApp – submit assignments, talk to friends, ask questions.” Many students use Zoom for more than four lessons every day, including core topics like English and Science, as well as extracurricular activities like dance or taekwondo. As a result, students spend a significant amount of time on their laptops or mobile devices. Parents who dislike technology and digital exposure, on the other hand, prefer classroom courses because “they complain about their children’s increased screen time.”

Due to the extended lockout and the necessity to do other domestic responsibilities, some parents find it difficult to assist their children with the online learning paradigm.

Teachers have also expressed dissatisfaction with their inability to establish “rapport with the youngsters,” as they do in school. They believe that because teachers only see their pupils online, they are unable to monitor “body language in class” and “their relationship with peers.” As a result, many professors claim that remote learning makes it difficult to engage students.

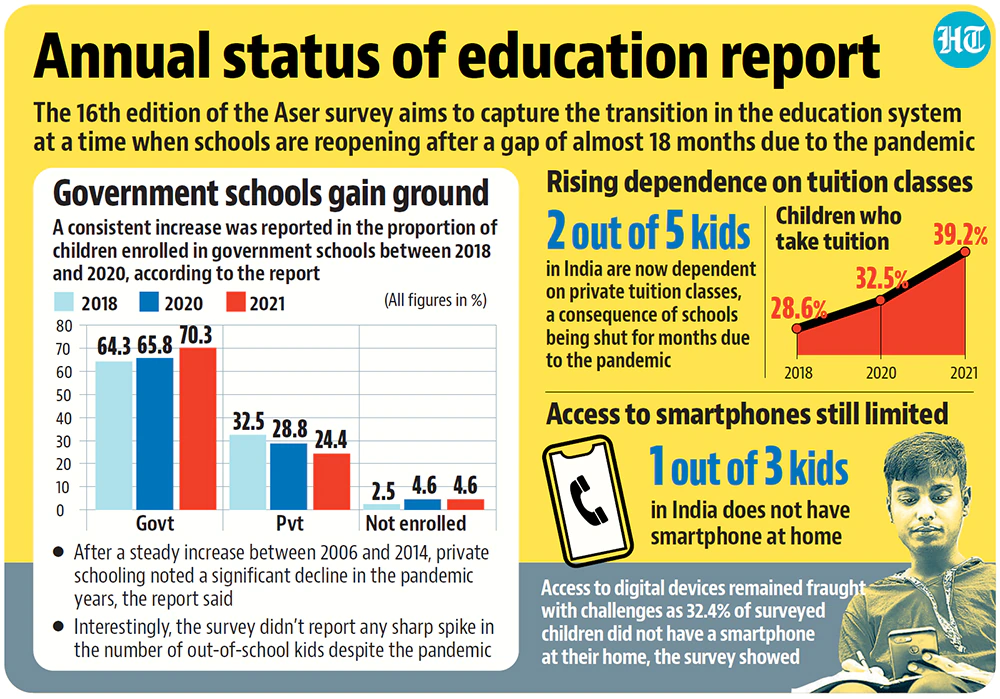

However, due to poor connectivity and lack of access to digital devices, many students, particularly in rural regions, have not received much, if any, online learning material. According to a poll, 42% of pupils aged 6 to 13 did not use any sort of remote learning during school closures. According to a report on India’s Key Indicators of Household Social Consumption on Education, only 15% of rural families had access to the Internet, compared to 42% of urban households. Many students struggled because they lacked personal gadgets, had poor internet connections, couldn’t afford an internet membership, schools didn’t supply resources, or couldn’t grasp the online curriculum.

Impact of School Closures

The consequences of the school closures are far-reaching, affecting nearly every aspect of human development. We’ll concentrate on two crucial areas: education and nutrition.

Education

Many students have fallen behind in their studies as a result of the protracted school closure and the aforementioned poor reception of online learning. Many have forgotten pre-pandemic studies and lack the requisite core skills to handle a formal grade-based curriculum. According to a poll of 1,400 low-income pupils, the extended school closure has resulted in a “four-year learning deficit.” This means that “a student who was in Grade 3 before COVID-19 is now in Grade 5 and will shortly enter middle school, but has reading ability comparable to a Grade 1 student.”

“Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the school has been shuttered.” Nearly 35% of pupils in cities and 42% of kids in villages were unable to read more than a few letters. Similarly, Jean, an economist, described how the youngsters he visited in Jharkhand’s primary schools “could not recognize vernacular letters or compose words.” This example corresponds to a broader survey of 16,000 students in grades 2 through 6 from five states, which found that 92% had lost at least one language ability and 82% had lost at least one arithmetic ability. As a result, the 18-month closure of the school has resulted in stunted or regressing educational growth.

The rise in the number of dropouts has been particularly upsetting. Prior to the pandemic, education in rural regions was viewed as a trade-off, with going to school implying that parents would be unable to help their children earn a living on the farm or in a business. Many families were unemployed, financially stressed, or in debt throughout the pandemic. As a result, many parents in rural areas may decide not to send their children back to school in order to help their families financially. As of mid-July 2021, 60,000 dropouts were estimated in Andhra Pradesh, with barely 25% of Grade 1 students enrolled. In the younger age categories, the number of children who are not in school has climbed dramatically.

A big number of dropouts at such a young age could have a long-term impact on a generation’s output. It’s also possible that girls are dropping out of school at a higher rate than boys, jeopardizing recent progress in decreasing the gender education gap.

Wealthier urban parents, on the other hand, who have been able to assist their children with online learning will be able to send their children back to school at grade level. “The closure policy appears to be targeted to the interests of urban middle-class youngsters, who, unlike many of their rural counterparts, are safe at home and able to study online,” according to Economist Drèze. Similarly, compared to girls, more guys were able to devote time to their education and had access to phones that allowed them to participate in online learning. Instead, 71% of females from low-income families were helping with domestic duties, compared to 38% of boys. Most families choose to send just their sons to after-school supplementary classes if they can afford it.

Even if the sons are younger, parents prefer to focus on the son’s education since females will marry and leave the household, whereas the son will stay to care for his parents. [50] This demonstrates that, while all kids had the experience of an extended school closure, the impact on education differed by class and gender.

Conclusion

The growing gap between privileged children who have been able to continue their education online and less privileged children (especially girls) who have struggled to access online learning during the extended school closures will have long-term implications for social mobility and human capital formation. The following findings are consistent with studies that suggest that social mobility is highest in metropolitan areas with higher consumption, employment, and “high average education levels.” The rich children are already at a disadvantage as a result of this. According to the report, while India’s economic growth has helped a large portion of the people, it has had little effect on the chances of upward mobility for the lower classes and castes.

Furthermore, sons have had more prospects for upward mobility than daughters, while daughters from Muslim, Schedule Caste, and Schedule Tribe families have had fewer opportunities. Given India’s current Social Mobility Index ranking of 76th out of 82 countries, the prospect of equitable opportunity for advancement does not appear promising. From the 1950s to the 1980s, upward mobility “little changed.”

However, the value of education must not be overlooked. In fact, educational achievements are the “only” way to quantify intergenerational social mobility, according to a research. Education is a critical component of upward social mobility, particularly in the early years.

Long-term school closures could cost India more than US$400 billion in future profits, as well as causing social difficulties, income inequality, and a ceiling on upward mobility. As a result, prioritizing the education sector is critical not just for students and instructors, but also for the country’s future development.